the Georgica Mystique

If you have any doubt that there's a mystique to Georgica, just consider how the name is appropriated for luxury goods and services. Kate Spade sells-in an improbable but cheerful pairing of words-a Georgica Beach bralette; Victoria Beckham and Gilt offer Georgica dresses; Jack Rogers has Georgica sandals; and both Canvas Home and Bungalow 5 sell chairs tagged "Georgica." Meanwhile, Georgica Advisors will watch over your investments, and you can reside in a glass-walled Manhattan condominium building called the Georgica.

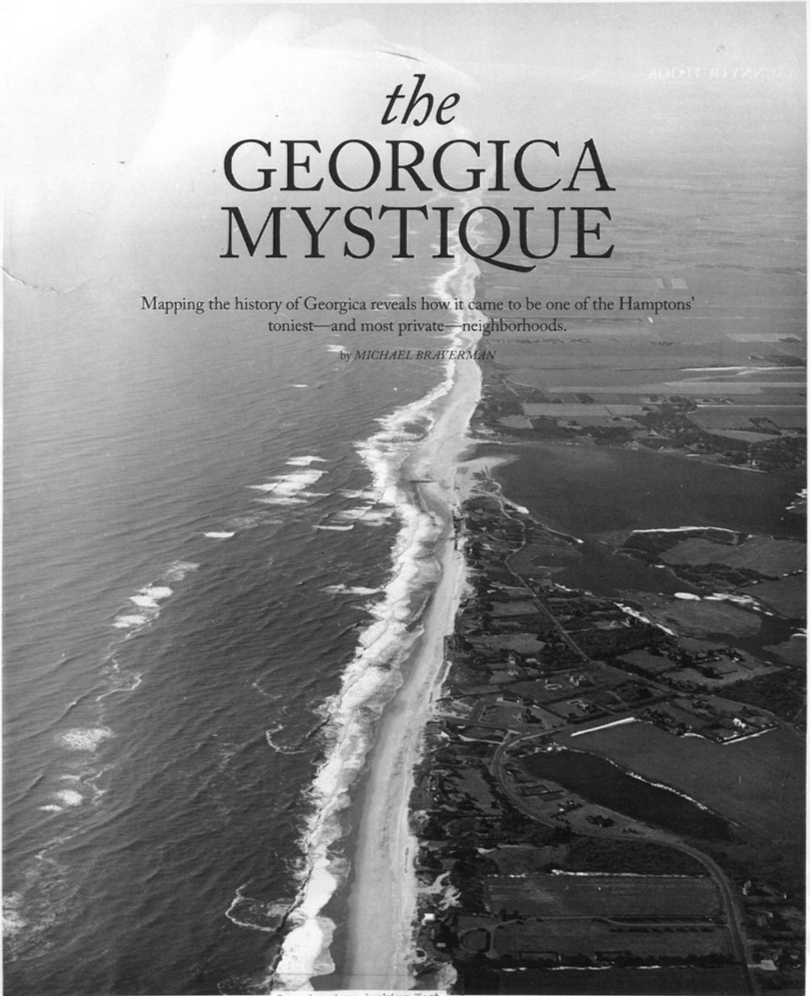

Borrowing the names of glamorous places for commercial use is nothing new, of course. More surprising to local residents is that the name Georgica, beyond becoming an area buzzword and brand, is recognized even outside the Hamptons. But if Georgica the name is marketable, Georgica the neighborhood is harder to pin down. If you want to be prosaic, you could call it a place on a map, though it has no official status and no exact boundaries. But for anyone who knows the Hamptons, Georgica evokes history and charisma, character and a complexity-a mystique, if you will, that goes beyond geography. You might look around and see sand and water and the green lawns of large estates; you might focus on the natural beauty that, in certain places and at certain times, can be extraordinary. But beyond the observable, you're feeling the star power well mannered and tasteful, but still 24k star power.

At Georgica's center-conceptually if not quite geographically-is Georgica Pond, ringed with some of the most expensive residential real estate in the country. Current prices range from $8.75 million for a small house on an inlet to $140 million for a major pond front estate. Radiating from the pond are the neighborhoods that embody the Georgica mystique.

The Georgica Association, known to old-timers as the Settlement, fronts the Atlantic Ocean and the western shore of the pond. This closed-off community with private roads dates back to the late 19th century, when William H.S. Wood acquired about 40 acres and sold lots to friends hand-picked from his own social background. Wood purchased more land until the settlement !,>Tew to about 137 acres, with his immediate heirs continuing the custom of selling to like-minded friends. But strict covenants came along with those Association deeds. Among the long list of don'ts was a restriction on saloons and beer halls. At that time well mannered people in the Hamptons did not drink in public-the Maidstone Club, for example, didn't have a bar until after Prohibition ended in 1933.

For Wood and the wealthy families that built fairly unassuming shingle houses on large lots fronting or close to the pond, mere deed covenants did not suffice to protect their investments. In its very early days, the Association enhanced its seclusion by rerouting old settler roads and eliminating access to a wooden causeway crossing the water to East Hampton Village (this is why Wainscott Main Street now ends so abruptly). From today's perspective, privacy could not have been much of an issue: Wainscott at the time was nothing but a tiny farm community with a one-room schoolhouse, a chapel, and a general store with a cracker barrel.

It may sound imperious to us now, but such high-handed manipulation was accepted in that era, and similarly restrictive actions were taken by owners on the east side of the pond. The maneuvering succeeded in keeping the Georgica Association private and helped establish and extend its upper-crust reputation.

One old colonial road, for instance, was partly erased and partly appropriated by the Association. It had provided ocean access for local families back when haulseining was part of their fishing livelihood, so a replacement road had to be built through the farm fields outside the Association. That once-utilitarian road is now the very posh Beach Lane, home to Toni Ross and Ronald Lauder, among other names of note. And the Association has lent its own landing to local baymen.

Social patterns set in the 19th century lasted a few generations, but attitudes slowly changed, and since at least the 1980s the Association has been more attuned to the world we live in. Residents might not share a common background any longer, but they do share a recognizable lifestyle. Recent buyers, who paid breathtaking prices to have such a deluxe address, are among the wealthiest residents. Some legacy families might not have the same sort of disposable income, but they do have immense reserves in inherited real estate. The purpose of the Georgica Association is not to be all-embracing, but it is inclusive specifically for a group of affluent, family and home-oriented people with a stake in maintaining their community's natural environment and customs.

Old-money style is the prevailing code. Decorum rules. No one, old or new, flaunts their wealth. Instead of a clubhouse (forbidden by the covenants), there's a bare-bones beach pavilion, and people compete with one another only in tennis tounaments and sailing races, not in extravagance. Clambakes are preferred to catered hors d'oeuvres, and afternoon get-togethers to evening soirees.

Simply owning and residing there does not ensure membership in the Georgica Association, with use of its tennis courts or a place to launch your Beetle Cat Conversely, select residents living close to the Association (Aerin Lauder is one) are members. Traditions large and small-such as Saturday-afternoon baseball games or a picnic for the regatta awards-have endured for generations and still shape the residents' mind-set.

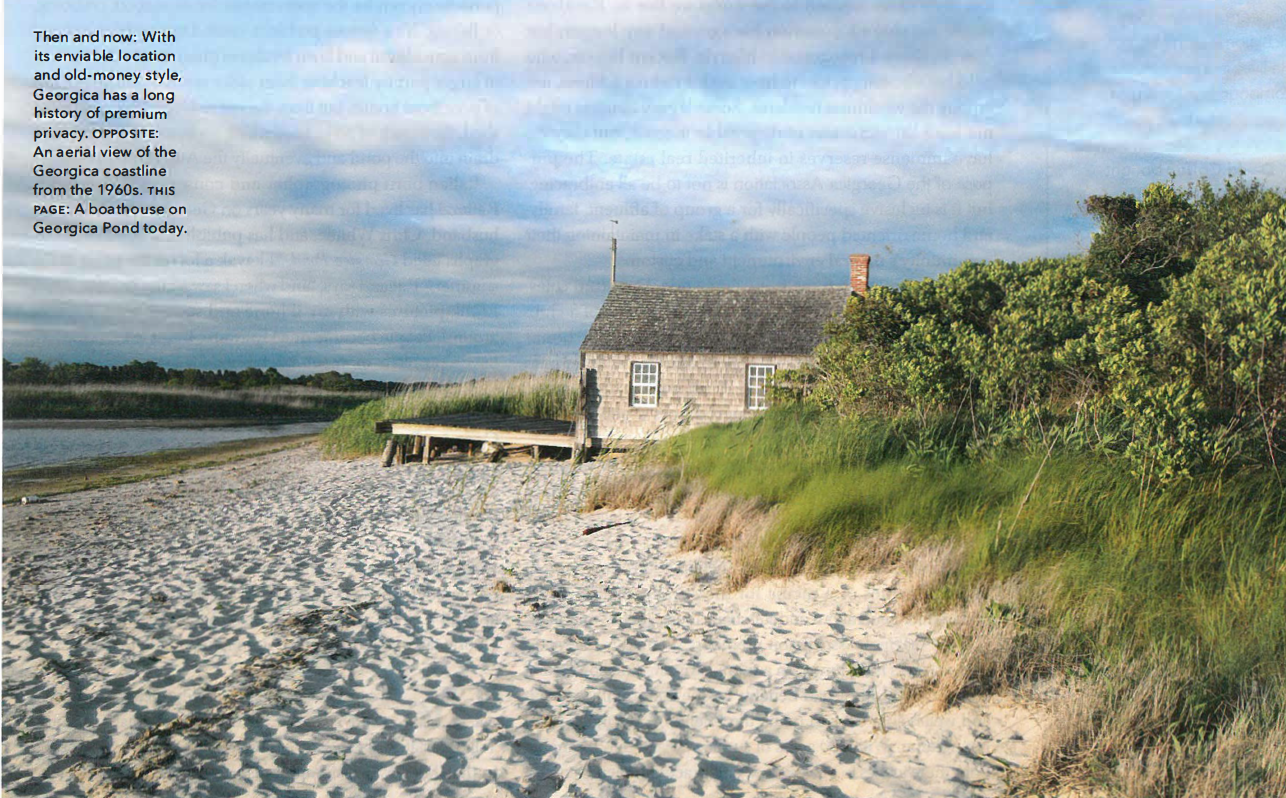

If the original Association members seemed insular, current residents have turned in a more altruistic direction, taking an approach with broad benefits for the community's health and well-being. Case in point: the Friends of Georgica Pond Foundation. With 290 acres of surface area, a depth ranging from mere inches to only six feet, and brackish water, Georgica Pond in recent years has been home to toxic algae blooms that periodically render the water unsafe for recreation, crabbing, or fishing. It's a serious problem, caused in part by the runoff from agricultural and lawn fertilizers (think trophy lawns) and in larger part by leaching from older septic systems, not just of pond front homes but from the entire Georgica Pond watershed, thousands of acres from which surface and groundwater drain into the pond and eventually the Atlantic.

Italian-born photographer and conservationist Priscilla Rattazzi has lived for many years on Georgica Pond with her husband, Chris Whittle, and has published a book of photographs titled Georgie a Pond. "I kayak a lot on the pond in the summer," Rattazzi says, "and when I saw all the floating algae, I took pictures with my iPhone and started sending them around. People became quickly aware. It was a 'Houston, we have a problem' moment. We formed the Friends of Georgica Pond Foundation in the fall of 2014 after my husband said, 'You need to become the Central Park Conservancy of Georgica Pond."'

The nonprofit organization aims to improve the health of the ecosystem throughout the watershed; as a first step, it's conducting a two-year scientific study with the Stony Brook University School of Marine and Atmospheric Sciences. As Rattazzi explains, "When I turned 60 last summer, I had a picnic on the beach with a dozen close friends, and we went around a circle, expressing wishes. Mine was and still is for Georgi ca Pond to improve before I am too old to care."

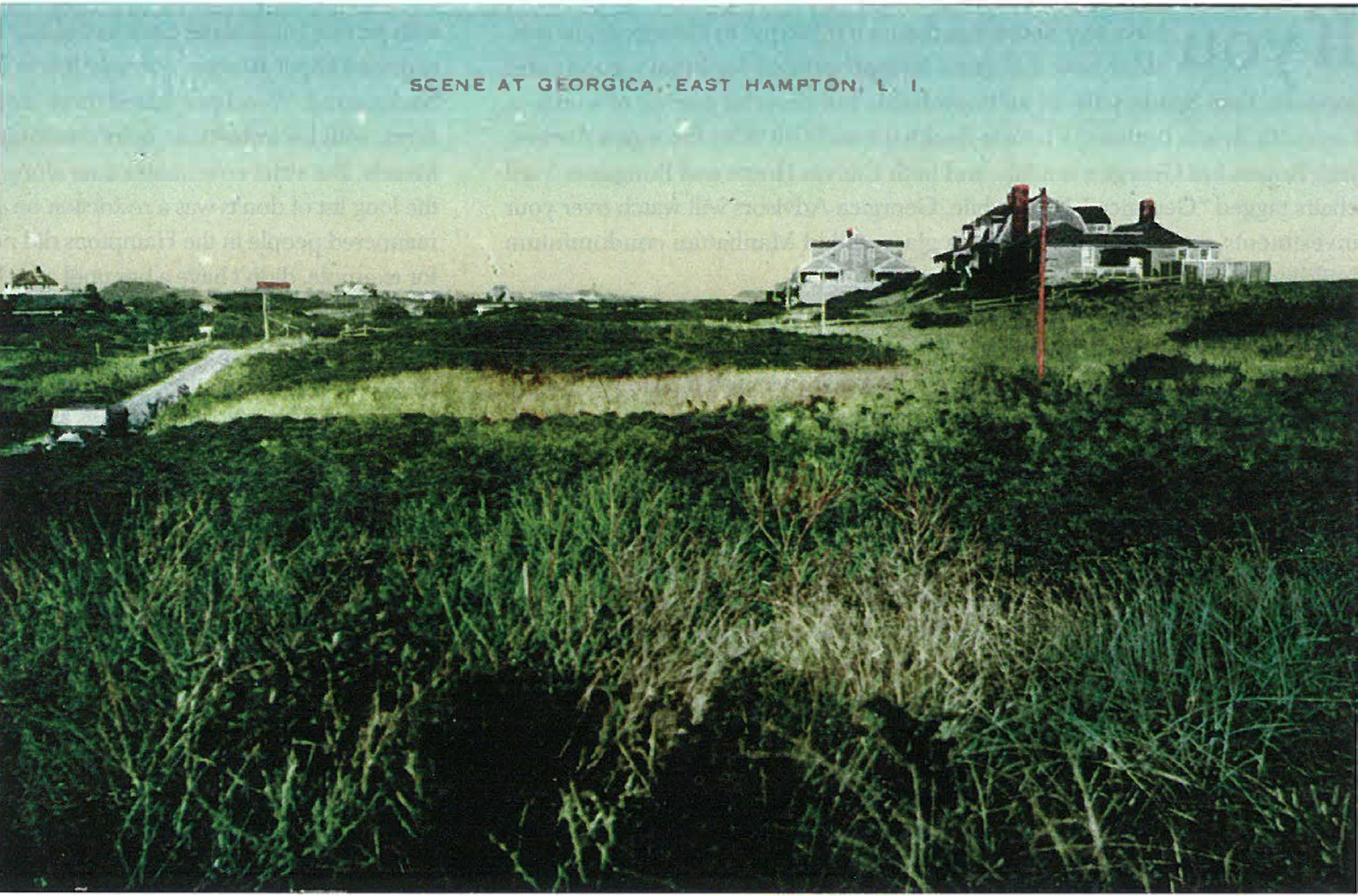

The area customarily called Georgica is composed of the western portion of the East Hampton Village estate area and the eastern shore of the pond. It began in the 1880s as a residential resort or "summer colony," as visitors from New York moved from Main Street or Apaquogue boarding houses to cottages they rented or owned. Getting there wasn't easy: Travelers took either a train and a horse drawn bus, or an overnight packet boat and a three-passenger coach. The colony gradually expanded after the Long Island Rail Road extended its tracks to East Hampton in 1895. The newcomers surprised locals with the novel idea of swimming in the ocean for recreation.

The clergy and people important in business and the arts arrived, but Georgica had no high-society pretensions in the manner of Newport or even Southampton. Rather than opulent mansions, their architectural propensity ran to the shingle style, using frame construction and cedar roofs and sidewalls, and a studied lack of ornament, just as the vernacular local dwellings did. No matter how large, they were still called cottages, and nearly all had a graceful, subdued aesthetic that prevails to this day. With exceptions, of course, new homes in the Georgica estate area are less massive and imposing than new construction in Sagaponack, Bridgehampton, or its closest counterpart, the Southampton Village estate area. Owners seem to honor an unspoken rule in deferring to a restrained East Hampton architectural pattern.

Current residents reflect a social mix typical of the Hamptons, with banking, big business, law, real estate, the entertainment industry, and politics all represented. They are mostly from New York but hail also from the West Coast and Washington, DC. Bill and Hillary Clinton summered in a rented home on Georgica Beach in 2011 and 2012 but moved on after a reputed disagreement over the security deposit.

Frank Newbold of Sotheby's International Realty in East Hampton has decades of experience brokering the sale of Georgica properties, while observing what has changed and what remains the same. "Especially in this unsettled real estate market, there is always a flight to quality," Newbold says. "Georgica is a blue chip that resonates with both established residents and newcomers. It's really exciting to see the redevelopment of properties to suit the tastes of younger buyers, but some Georgica basics remain constant. They appreciate the beautiful old trees, the proximity to the beach, and the reassurance that they live in a neighborhood that will continue to represent both a solid investment and the best of the classic East Hampton lifestyle."

New, younger buyers, whom Newbold understands and deals with, will determine Georgica's future. By choosing it above other prestigious neighborhoods, by putting their faith and substantial amounts of their money into a Georgica property, they become not just residents but stakeholders in preserving the privacy and preeminence and unique character that Georgica represents.

Even as the Hamptons change, Georgica remains an extraordinary, aspirational place, one of the most sought-after and beautiful in a part of the world where addresses make a critical social difference. Residents like Rattazzi remain staunch in their attachment, outsiders remain curious, and retailers remain enamored of the name-and the Georgica mystique.